This is a post that has been rattling around in my mind for a long time, but this has been the year when colleagues younger and older have asked me to please write this down. It's the first of a series of posts I'm going to do this summer, mostly to help myself remember what I need to know when I have forgotten what works. May it be of benefit to others as well.

NOTE: The book of Rudolf Dreikurs that has most deeply influenced my work is from 1964 and is called Children: The Challenge. While every cultural reference in this book may feel cringe-worthy and embarrassing to you, don't let that put you off. Dreikurs was a true master, and his framework and insights on every page ring as clear and true as the most finely tuned bell. It just happens to come from a different age. Don't be tossed away. Dreikurs' psychological methods and insights have a clarity you will not find elsewhere. Take what is beneficial to you and release what does not serve your needs.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Belongingness Comes First

In the child's mind, belonging is a life-or-death question.

The fundamental insight of Adlerian child psychology -- and of Adler's disciple Rudolf Dreikurs, who originated so many of the parenting concepts we now take to be obvious -- is that every child is driven to seek out belonging. The behaviors a kid manifests are designed to achieve their survival goal of secure belonging.

How can this be used in the classroom? Well, if a child enters a new situation and immediately experiences a sense of belonging, then things will tend to run smoothly. The child will read the room, unconsciously relax, and dive into the stream of seamless and happy participation.

Sounds easy, right? :)

In practice, it can be challenging to foreground belongingness in the classroom -- and to keep it in the foreground. It took me years to let go of my first teacher impulse to talk first and engage second. The way I've found best to implement belongingness is by consistently using a non-spoken daily structure that is impossible to ignore. When students walk into my classroom, the first thing they see projected on the screen is a "Welcome to Geometry!" slide with the instructions for the day. The very moment that class begins, I press "play" on my slide and the thundering drum fill from the Hawaii Five-O opening theme music crashes over the room. I have an ancient Bose speaker that amplifies the music.

It's impossible to ignore. But just in case students manage to ignore it, when it fades out, I start yelling. "Instructions are on the board! Read them and follow them! Let's go! Let's GO!"

It's important that the first time they hear my voice, it is in service to our shared collaborative mission. This establishes the ground rules of belongingness in my classroom. WE have a job to do together. I'm just here to encourage that along.

As we move into the heart of the first week, I use this structure to train students on how to work with Burning Questions. A Burning Question is a question about the previous day's work that students can't answer for themselves. THAT is the proper use of the teacher. So the first segment of every class' instructions is to prepare for the Burning Questions segment of class. I'll take every BQ students have, but I don't accept the answer "all of them." That's lazy and threatens belongingness.

Once we've assembled our list of Burning Questions, we walk through worked examples, but the way I do worked examples is very different from what I've observed in other teachers' classrooms.

As Rudolf Dreikurs says, "We must observe the result of our... program and repeatedly ask ourselves, 'What is this method doing to my child's self-concept?" (Dreikurs, p. 39). As teachers we are always faced with the choice of encouraging independence, self-respect, and sense of accomplishment or undermining it. A huge part of what children are learning to develop through productive struggle -- psychologically speaking -- is a healthy ability to tolerate and manage frustrations. Obstacles are a critical fact of adult life. We need to support children in developing the courage to see productive struggle as another texture of adult life they can learn how to face and overcome. As Dreikurs puts it, encouragement -- not praise -- plays a crucial role in helping students develop the "self-respect and sense of accomplishment" they will need to find their place in our world. (Dreikurs, p. 39)

Burning Questions is a Narrated Thought Process

The key to encouraging students' courage during Burning Questions is not to do any part of the problem that students can do for themselves. Burning Questions is a profoundly interactive segment of class.

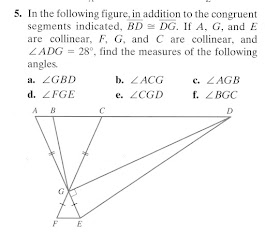

In practical terms, this means that demonstrating worked solutions requires modeling the metacognitive questions I would ask myself as a learner when I encounter a math problem of this type and find myself stumped. Modeling courage is essential. Students always already know something. And since what they know is the best thing they know, I use my understanding of their ZPD (Zone of Proximal Development) to find a simpler starting-point question that they can answer. This is usually a question about identifying the situation at hand in the problem. What kind of triangle do we have here? Do we have parallel lines? What kind of angle pair are angles 1 and 8 in the diagram? Do we have an altitude-to-the-hypotenuse situation here?

Encouraging students to name -- and use names for -- different mathematical situations is a critical part of my pedagogy. It enables me to ask them dozens or even hundreds of times whether we can spot one of our familiar important mathematical situations

I break down and ask the questions; if the students don't provide the answers to my much-simpler questions, then we simply don't progress. My wait time game is strong. I can sit silently, blinking, for three whole minutes, if need be.

Belongingness dictates students' need to collaborate to find answers. I name and narrate behaviors that I see which are positive and constructive learning behaviors which everyone in the room can do. "I see some people flipping back through their notes, looking up different situations. That seems like a good idea to me." More pages start getting flipped. Quiet conversation ensues at different tables. Students point out possibly relevant parts of their previous days' notes.

Eventually somebody brave will pipe up with an idea. I will repeat the idea for the whole class and ask if that makes sense to them. I will often take a vote. I am not some deified source of right and wrong answers. I am actively trying to encourage them to rely on courage and on each other. We'll take a vote. Only then will I confirm whether or not this makes sense.

Wrong answers are fine and we honor them by interrogating them and passing by quickly. They give me an opening to ask more clarifying and refining questions about key properties and distinctions. I tell students that spotting known mathematical situations is like bird-watching. You need a field guide and practice identifying the distinguishing characteristics of different situations. This is how people learn.

This is my process for modeling courage and resourcefulness during productive struggle. Mine might work for you, or you might need to find your own on-ramp.

Students get a lot faster at this interactive process. At the beginning of the school year, I may have to wait minutes before moving on. Within a few weeks, it will only take a matter of seconds for students to pipe up with answers for each questions.

"What kind of situation do we have here?"

"Altitude to the hypotenuse situation."

"Good. What pieces of the situation do we know? Which lengths do we have? Which lengths do we need to find?"

Never answer a question that the students can answer for themselves or for each other. This is how we cultivate courage and endurance for productive struggle.

Piece by piece, question by question, we walk through the problem together. Belongingness is non-negotiable. Whole-class segments not only teach participation and collaboration skills; they enact belongingness. Even if you are totally off-task, absorbed in texting, or feeling heartbroken over your relationship break-up or something even worse, during whole-class segments, you still belong.

As Dreikurs puts it, "All comparisons are harmful." (Dreikurs, p. 44) Whole-class segments are not the time to yell at a kid for being glued to their phone. If you have to have that conversation with a kid, do it in private. "Her abilities will increase only if her confidence is restored." (Dreikurs, p. 44). The ultimate larger goal is to encourage each student to reach "the point where [they] will enjoy learning... and may find out how much more capable [they] are than [they] have thought till now." (Dreikurs, p. 45)

The Enemy of Belongingness is Discouragement

But if a child has become discouraged, their focus will shift from participational and cooperative behaviors toward less constructive behaviors that are unconsciously designed as defense mechanisms to protect them against their perceived failure to achieve belonging.

This is the most important insight a teacher can integrate into their classroom management orientation.

These are not deliberate strategies. These are observed and catalogued patterns of behavior that arise when a child fails to achieve successful belonging.

This is good news for classroom teachers. If you can make sense of and spot these behaviors, you can generally find solutions for redirecting them into pro-social behaviors that will be more satisfying for everybody involved, including both you and the child.

When I first read Dreikurs' analysis of the four mistaken goals of the discouraged child, I had a breakthrough in my understanding of students' misdirected behaviors. I'm writing this down because I want other teachers to be able to make sense of this too. It's so much easier to deal with when you have a validated framework for making sense of what's going on.

Here is Dreikurs' 30,000-foot perspective, with one modern update from me in brackets:

Children want desperately to belong. If all goes well and the child maintains his courage, he presents few problems. He does what the situation requires and gets a sense of belonging through his [success] and participation. But if he becomes discouraged, his sense of belonging is restricted. His interest turns from participation in the group to a desperate attempt at self-realization through others. All his attention is turned toward this end, be it through pleasant or disturbing behavior, for, one way or another, he has to find a place. There are four recognized "mistaken goals" that such a child can pursue. It is essential to understand these mistaken goals if we hope to redirect the child into a constructive approach to social integration. (Dreikurs, p. 58)

Once I started understanding student misbehaviors as falling into one of the four mistaken goals of a discouraged child, it became much easier to find appropriate and effective methods for redirecting student energies in healthier and more constructive ways.

I want to emphasize that there are two important elements to healthy classroom management here. One belongs to the teacher, keeping a clear understanding of the situation, not allowing oneself to get triggered, refraining from reacting to the triggering behavior, and maintaining healthy boundaries to preserve your own sanity. The other belongs to the student who is suffering and acting out in one of the four mistaken ways. The student needs to feel seen, understood, appreciated, and guided in a healthier way.

But because the student is still developmentally a child -- with a child's incompletely formed sense of judgment and executive function -- plus whatever other factors are at play in the child's outside life situation, this is one of the most important situations in which to understand that telling is not teaching. This is the real genius of Dreikurs' approach. He understands that the language of actions is the only way in which the adult can successfully reach the child with these messages. It has to take place at an unconscious level. And it is by taking this approach and following it all the way through that a teacher can reach and encourage the student to follow the better, more effective and healthier path.

To put it another way, we have to use psychodynamic wisdom in order to achieve psychological goals.