The writing method we used was a combination of the Jane Shaffer method and Six Traits. Every teacher in the district had been trained on the method, and collaborative rubrics and projects had been developed over the years. The method was flexible, but we all agreed on certain basic components. We used Jane Shaffer's method of color-coding, from elementary through middle school. This meant that every student in the district developed a common understanding of what a topic sentence is, what a claim is, how we use evidence to support our claims, and how we use reasoning to tie things together. I believe it is still one of the highest-performing writing districts in California.

One of our signature practices was that we gave a fall writing assessment and a spring writing assessment. In middle school it was a two-day affair, tied to the literature curriculum. Time was allocated for pre-writing and writing.

And then we teachers were given an on-campus release day so we could read and score holistically — together. We double-scored each sample, using a rubric and highlighters.

It drove us crazy, but it also enabled us to see patterns. And because we could see patterns, we could adapt instruction to address the gaps or needs we identified.

Shouldn't this be the norm for instruction?

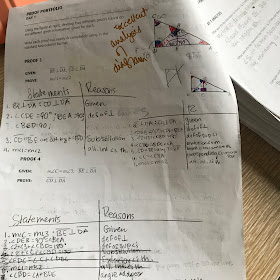

I have long wanted to use this approach with my teaching of proof in high school, but this was the first year I got my act together to run my own personal pilot program. I don't have a colleague with whom to work on this, so I went it alone. I created a four-day project that and gave them one day's worth of stuff to work on each day.

Here is the zip file with all four days' worth of assignments: https://drive.google.com/open?id=1Zz3KlZ5zVO9K_0S4dW822hNJ9X4VtUdVThe secret of doing an assignment like this is radical: you have to relinquish control. You cannot be the only one giving students feedback. In fact, there is so much practice here, it is completely impossible. That is good. One thing I have learned as a writer and as a teacher of writing is that you learn how to write by writing a lot. The same is true with proof and proving. Students need space to immerse themselves and not worry about whether every mark they make is "right" or "wrong."

So each day had its "stuff." Four small proofs a day, plus reflection and peer review. Then more the next day.

The complaints and lamentations were filled with drama. "OH MY GOD, DR. S — THAT ASSIGNMENT WAS HARD." But they could tell that they had accomplished something.

My assessment strategy was to be rigorous about completion but merciful with points. It was only worth a quiz grade (100 points), and my default score for students who completed every section was a 95. There are rewards for following instructions. Missing sections or components left blank cost more points.

But none of that matters. My goal was to get students doing a LOT of proof -- writing shitty first drafts, comparing notes with each other, and using a rubric to assess each other's work. Dogen Zenji said, "When you walk in the mist, you get wet."

And it seems to have made a difference.

I am excited to see what happens on the next major test that includes a proof. Photos of student work to follow.

As always, let me know what you think and what happens if you use this!